What Fashion Era Was Late 1700's

Fashion in the xx years between 1775–1795 in Western culture became simpler and less elaborate. These changes were a effect of emerging modern ideals of selfhood,[i] the declining fashionability of highly elaborate Rococo styles, and the widespread cover of the rationalistic or "classical" ethics of Enlightenment philosophes.[2]

This French apparel, c. 1775 has the fitted back of the robe à l'anglaise and skirt draped à la polonaise. LACMA

Enlightenment concept of "fashion" [edit]

According to some historians, information technology was at this time when the concept of way, as it is known today, was established (others date it much earlier). Prior to this point, clothes as a means of self-expression were limited. Guild-controlled systems of production and distribution and the sumptuary laws made vesture both expensive and difficult to learn for the majority of people. Yet, past 1750 the consumer revolution brought about cheaper copies of fashionable styles, allowing members of all classes to partake in stylish wearing apparel. Thus, fashion begins to stand for an expression of individuality.[3] [4]

French Revolution [edit]

As the radicals and Jacobins became more powerful, at that place was a revulsion against loftier-fashion considering of its extravagance and its association with royalty and elite. It was replaced with a sort of "anti-fashion" for men and women that emphasized simplicity and modesty. The men wore plain, dark clothing and brusk unpowdered hair. During the Terror of 1794, the workaday outfits of the sans-culottes symbolized Jacobin egalitarianism.

High fashion and extravagance returned to France and its satellite states nether the Directory, 1795–99, with its "directoire" styles; the men did non return to extravagant customs.[5] These trends would reach their height in the classically-styled fashions of the late 1790s and early 19th century.[6] For men, coats, waistcoats and stockings of previous decades continued to exist fashionable across the Western world, although they too changed silhouette in this period, condign slimmer and using earthier colors and more matte fabrics.[7]

Women's mode [edit]

Overview [edit]

Woman's silk brocade shoes with straps for shoe buckles, probably Italy, 1770s, LACMA

Women'southward wear styles maintained an emphasis on the conical shape of the torso while the shape of the skirts changed throughout the menses. The wide panniers (holding the skirts out at the side) for the nigh part disappeared by 1780 for all merely the nigh formal courtroom functions, and false rumps (bum-pads or hip-pads) were worn for a fourth dimension.

Marie Antoinette had a marked influence on French fashion beginning in the 1780s. Around this fourth dimension, she had begun to rebel against the structure of court life. She abolished her morning time toilette and escaped to the Petit Trianon with increasing frequency, leading to criticism of her exclusivity by cutting off the traditional correct of the aristocracy to their monarch. Marie Antoinette found refuge from the stresses of the rigidity of court life and the scrutiny of the public eye, the ailing wellness of her children, and her sense of powerlessness in her marriage by carrying out a pseudo-country life in her newly constructed hameau.[viii] She and an elite circle of friends would dress in peasant clothing and straw hats and retreat to the hameau. Information technology was out of this practice that her fashion of dress evolved.

By tradition, a lady of the court was instantly recognizable by the panniers, corset, and weighty silk materials that constructed her gown in the style à la française or à 50'anglaise. By doing abroad with these things, Marie Antoinette's gaulle or chemise á la Reine stripped female aristocrats of their traditional identity; noblewomen could now be confused with peasant girls, disruptive long continuing sartorial differences in class. The chemise was made from a white muslin and the queen was further accused of importing foreign fabrics and crippling the French silk industry.[9] The gaulle consisted of thin layers of this muslin, loosely draped effectually the body and belted at the waist, and was often worn with an frock and a fichu. This trend was quickly adopted by fashionable women in France and England, but upon the debut of the portrait of Marie Antoinette by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, the clothing fashion created a scandal and increased the hatred for the queen.[8] The queen'southward clothing in the portrait looked like a chemise, zippo more than a garment that women wore under her other clothing or to lounge in the intimate space of the private boudoir. It was perceived to be indecent, and particularly unbecoming for the queen. The sexual nature of the gaulle undermined the notions of status and the ideology that gave her and kept her in power. Marie Antoinette wanted to exist individual and individual, a notion unbecoming for a member of the monarchy that is supposed to act every bit a symbol of the country.

When Marie Antoinette turned 30, she decided it was no longer decent for her to clothes in this fashion and returned to more acceptable ladylike styles, though she still dressed her children in the style of the gaulle, which may have continued to reverberate badly on the stance of their mother even though she was making visible efforts to rein in her own previous fashion excess.[9] However, despite the distaste with the queen's inappropriate fashions, and her own switch dorsum to traditional clothes later in life, the gaulle became a pop garment in both France and abroad. Despite its controversial beginnings, the simplicity of the style and material became the custom and had a great influence on the transition into the neoclassical styles of the tardily 1790s.[viii]

During the years of the French Revolution, women'southward dress expanded into different types of national costume. Women wore variations of white skirts, topped with revolutionary colored striped jackets, besides as white Greek chemise gowns, accessorized with shawls, scarves, and ribbons.[10]

Past 1790, skirts were still somewhat full, but they were no longer manifestly pushed out in any particular direction (though a slight bustle pad might withal be worn). The "pouter-pigeon" front came into mode (many layers of cloth pinned over the bodice), just in other respects women'due south fashions were starting to be simplified by influences from Englishwomen'southward country outdoors wear (thus the "redingote" was the French pronunciation of an English "riding coat"), and from neo-classicism. By 1795, waistlines were somewhat raised, preparing the way for the evolution of the empire silhouette and unabashed neo-classicism of belatedly 1790s fashions.

Gowns [edit]

The usual fashion at the beginning of the menses was a low-necked gown (normally called in French a robe), worn over a petticoat. Nearly gowns had skirts that opened in front to show the petticoat worn beneath. As part of the general simplification of dress, the open bodice with a separate stomacher was replaced by a bodice with edges that met center front end.[xi]

The robe à la française or sack-dorsum gown, with back pleats hanging loosely from the neckline, long worn equally court fashion, made its final appearance early on in this catamenia. A fitted bodice held the front of the gown closely to the figure.

The robe à l'anglaise or shut-bodied gown featured dorsum pleats sewn in place to fit closely to the body, and then released into the skirt which would be draped in various means. Elaborate draping "à la polonaise" became fashionable past the mid-1770s, featuring backs of the gowns' skirts pulled up into swags either through loops or through the pocket slits of the gown.

Forepart-wrapping thigh-length shortgowns or bedgowns of lightweight printed cotton textile remained fashionable at-domicile morn habiliment, worn with petticoats. Over time, bedgowns became the staple upper garment of British and American female working-class street wear. Women would besides often article of clothing a neck handkerchief or a more formal lace modesty piece, particularly on lower cut dresses, oft for modesty reasons.[12] In surviving artwork, there are few women depicted wearing bedgowns without a handkerchief. These large handkerchiefs could be of linen, plain, colored or of printed cotton for working wear. Wealthy women wore handkerchiefs of fine, sheer fabrics, often trimmed with lace or embroidery with their expensive gowns.[13]

Jackets and redingotes [edit]

An informal alternative to the dress was a costume of a jacket and petticoat, based on working class fashion merely executed in effectively fabrics with a tighter fit.

The caraco was a jacket-similar bodice worn with a petticoat, with elbow-length sleeves. By the 1790s, caracos had full-length, tight sleeves.

As in previous periods, the traditional riding habit consisted of a tailored jacket similar a man'due south coat, worn with a loftier-necked shirt, a waistcoat, a petticoat, and a lid. Alternatively, the jacket and a simulated waistcoat-front might exist a made every bit a single garment, and later in the period a simpler riding jacket and petticoat (without waistcoat) could be worn.

Another culling to the traditional habit was a coat-dress called a joseph or riding glaze (borrowed in French every bit redingote), unremarkably of unadorned or simply trimmed woolen fabric, with full-length, tight sleeves and a broad collar with lapels or revers. The redingote was afterward worn as an overcoat with the low-cal-weight chemise dress.

Underwear [edit]

The shift, chemise (in French republic), or smock, had a depression neckline and elbow-length sleeves which were full early in the period and became increasingly narrow as the century progressed. Drawers were not worn in this period.

Strapless stays were cutting loftier at the armpit, to encourage a woman to stand up with her shoulders slightly dorsum, a fashionable posture. The fashionable shape was a rather conical trunk, with large hips. The waist was not especially modest. Stays were usually laced snugly, only comfortably; simply those interested in farthermost fashions laced tightly. They offered back support for heavy lifting, and poor and middle form women were able to piece of work comfortably in them. As the relaxed, state mode took concur in France, stays were sometimes replaced by a lightly boned garment called "un corset," though this style did not reach popularity in England, where stays remained standard through the finish of the menstruum.

Panniers or side-hoops remained an essential of court fashion but disappeared everywhere else in favor of a few petticoats. Free-hanging pockets were tied around the waist and were accessed through pocket slits in the side-seams of the gown or petticoat. Woolen or quilted waistcoats were worn over the stays or corset and under the gown for warmth, as were petticoats quilted with wool batting, especially in the common cold climates of Northern Europe and America.

Footwear and accessories [edit]

Shoes had high, curved heels (the origin of modernistic "louis heels") and were made of fabric or leather. Shoe buckles remained stylish until they were abased along with high-heeled footwear and other aloof fashions in the years after the French Revolution,[fourteen] [fifteen] The long upper also was eliminated, essentially leaving but the toes of the pes covered. The slippers that were ordinarily worn with shoes were abandoned because the shoes had go comfy enough to be worn without them. Fans connected to exist popular in this time period, however, they were increasingly replaced, outdoors at to the lowest degree, past the parasol. Indoors the fan was still carried exclusively. Additionally, women began using walking sticks.[16]

Hairstyles and headgear [edit]

Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, was one of the most influential figures in fashion during the 1770s and 1780s, specially when it came to hairstyles.

The 1770s were notable for extreme hairstyles and wigs which were congenital up very high, and oftentimes incorporated decorative objects (sometimes symbolic, as in the case of the famous engraving depicting a lady wearing a large ship in her hair with masts and sails—called the "Crew à l'Indépendance ou le Triomphe de la liberté"—to celebrate naval victory in the American war of independence). These coiffures were parodied in several famous satirical caricatures of the period.

By the 1780s, elaborate hats replaced the former elaborate hairstyles. Mob caps and other "country" styles were worn indoors. Flat, broad-brimmed and low-crowned harbinger "shepherdess" hats tied on with ribbons were worn with the new rustic styles.

Hair was powdered into the early 1780s, but the new way required natural colored pilus, frequently dressed simply in a mass of curls.

Style gallery [edit]

1775–1789 [edit]

-

1 – 1776

-

2 – 1778

-

3 – 1780

-

iv – 1783

-

5 – 1784–87

-

six – 1785

-

vii – 1786

-

8 – 1787

-

9 – 1787

-

10 – 1789

- Lady Worsley wears a reddish riding habit with war machine details, copying those of the compatible of her husband's regiment (he was abroad fighting the American rebels) on the cutaway coat and a buff waistcoat, 1776.

- Marie Antoinette wears panniers, a requirement of courtroom manner for the most formal state occasions, 1778

- The Ladies Waldegrave wear transitional styles, 1780–81, in their portrait by Reynolds. Their hair is powdered and dressed high, merely their white caracos, similar shorter dresses à la polonaise, have long tight sleeves.

- Marie Antoinette in chemise dress, 1783. She wears a sheer, striped sash and a wide-brimmed hat. Her sleeves are poufed, probably with drawstrings.

- French robe à l'anglaise with fashionable airtight bodice, 1784–87, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Marie Antoinette wears the popularized turban, with a scarf wrapped around it. Her neckband is heavy with lace, and her crimson petticoat is trimmed in fur, 1785.

- Fashion plate of 1786 shows a caraco and petticoat, worn with a wide-brimmed summertime hat of straw with elaborate trimmings.

- Miss Lawman, 1787, wears a chemise dress with patently sleeves and a narrow sash. She wears her hair down in a mass of curls nether her straw hat.

- The Marquise de Pezay and the Marquise de Rouge wear colorful dresses in the new style, one blue and one striped, with sashes and loftier-necked chemises beneath. The Marquise de Rougé wears a scarf or kerchief wrapped into a turban.

- Elizabeth Sewall Salisbury wears an oversized mob cap trimmed with a broad satin ribbon and a kerchief pinned high at the neckline. America, 1789.

1790–1795 [edit]

-

1 – 1790

-

2 – c. 1791

-

three – 1791

-

4 – 1792

-

5 – 1790s

-

6 – 1793

-

7 – 1793

-

viii – 1794

-

9 – 1795

- Redingote or riding coat of c. 1790, with "pouter-dove" front. This lady wears a mannish top hat for riding and carries her riding crop.

- Self-portrait of Rose Adélaïde Ducreux with harp.

- 1791 illustration of woman playing with an early on class of yo-yo (or "bandalore") shows slight bosom draping, which in more extreme form became the "pouter pigeon" look.

- Illustration of women's style from 1792

- Sketch past Isaac Cruikshank (father of George), showing both male and female heart-class English styles of the early 1790s.

- La Comtesse Bucquoi wears a sashed gown with a high-necked, frilled chemise beneath, a turban on her head, and a newly stylish blood-red shawl. 1793.

- Mrs. Richard Yates, 1793, wears a very conservative gown with a kerchief and a gathered mob cap with a large ribbon bow.

- María Rita de Barrenechea y Morante, Marchioness of la Solana

- The Duchess of Alba wears a simple white gown, with a red sash and bow on her low neckband. She wears her hair loose and gratuitous. This portrait shows the influence of French style in Spain at the end of the 18th century, 1795.

Caricature [edit]

-

Miss Shuttle-Erect (1776) compares women'south dresses and feathered headwear to the shuttlecocks used in the sport of Badminton.

-

In Post-obit the Manner (1794), James Gillray caricatured figures flattered and not flattered by the high-waisted gowns then in manner.

-

Isaac Cruikshank'due south caricature of a female French revolutionary, emphasizing colorful, mismatched wearing apparel (1794).

French mode [edit]

-

France, 1777

-

France, 1781

-

French republic, 1782

-

France, 1783

-

France, 1783

-

France, 1784

-

France, 1784

-

France, 1785

-

French republic, 1788

-

France, 1789

-

French republic, 1789

-

France, 1790

-

France, 1792

Castilian mode [edit]

-

Kingdom of spain, 1775

-

Kingdom of spain, 1778

-

Spain, 1783

-

Kingdom of spain, 1785

-

Spain, 1785

-

Spain, 1787

-

Kingdom of spain, 1789

-

Espana, 1789

-

Spain, 1790

-

Spain, 1792

-

Spain, 1794

-

Espana, 1794

-

Spain, 1795

-

Espana, 1795

-

Spain, 1795

-

Espana, 1795

Men'south manner [edit]

Overview [edit]

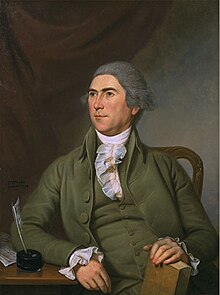

Elijah Boardman wears a cutaway tailored coat over a waist-length satin waistcoat and dark breeches. United States, 1789.

Charles Pettit wears a matching coat, waistcoat, and breeches. Coat and waistcoat have covered buttons; those on the coat are much larger. His shirt has a sheer frill downward the front. United states of america, 1792.

James Monroe, the concluding U.South. President who dressed according to an old-fashioned fashion of the 18th century, with his Cabinet, 1823. The president wears knee breeches, while his secretaries wear long trousers.

Pair of man's steel and gilt wire shoe buckles, c. 1777–1785. Los Angeles County Museum of Fine art, M.80.92.6a-b

Throughout the menstruation, men continued to wearable the coat, waistcoat and breeches. However, changes were seen in both the fabric used as well every bit the cutting of these garments. More attending was paid to individual pieces of the adapt, and each element underwent stylistic changes.[10] Under new enthusiasms for outdoor sports and country pursuits, the elaborately embroidered silks and velvets feature of "total dress" or formal attire before in the century gradually gave way to advisedly tailored woolen "undress" garments for all occasions except the almost formal.

In Boston and Philadelphia in the decades around the American Revolution, the adoption of plain undress styles was a conscious reaction to the excesses of European court dress; Benjamin Franklin caused a sensation by appearing at the French court in his own hair (rather than a wig) and the plain costume of Quaker Philadelphia.

At the other extreme was the "macaroni".

In the United states of america, simply the get-go 5 Presidents, from George Washington to James Monroe, dressed according to this fashion, including wearing of powdered wigs, tricorne hats and knee-breeches.[17] [xviii] The latest-born notable person to be portrayed wearing a powdered wig tied in a queue according to this way was Archduke John of Republic of austria (built-in in 1782, portrayed in c. 1795).[19]

Coats [edit]

By the 1770s, coats exhibited a tighter, narrower cutting than seen in earlier periods, and were occasionally double-breasted.[10] Toward the 1780s, the skirts of the coat began to be cutaway in a curve from the front waist. Waistcoats gradually shortened until they were waist-length and cut straight across. Waistcoats could be made with or without sleeves. Every bit in the previous menses, a loose, T-shaped silk, cotton or linen gown called a banyan was worn at home as a sort of dressing gown over the shirt, waistcoat, and breeches. Men of an intellectual or philosophical bent were painted wearing banyans, with their own hair or a soft cap rather than a wig.[20] This aesthetic overlapped slightly with the female fashion of the skirt and proves the way in which male and female fashions reflected one some other as styles became less rigid and more suitable for movement and leisure.[21]

A coat with a broad collar called a apron glaze, derived from a traditional working-grade coat, was worn for hunting and other country pursuits in both Britain and America. Although originally designed as sporting wear, apron coats gradually came into way as everyday habiliment. The frock coat was cut with a turned down collar, reduced side pleats, and small, round cuffs, sometimes cutting with a slit to allow for added movement. Sober, natural colors were worn, and coats were made from woolen material, or a wool and silk mix.[ten]

Shirt and stock [edit]

Shirt sleeves were full, gathered at the wrist and dropped shoulder. Total-dress shirts had ruffles of fine cloth or lace, while undress shirts ended in plain wrist bands. A small turnover neckband returned to fashion, worn with the stock. In England, clean, white linen shirts were considered of import in Men'south attire.[x] The cravat reappeared at the end of the period.

Breeches, shoes, and stockings [edit]

Equally coats became cutaway, more attention was paid to the cut and fit of the breeches. Breeches fitted snugly and had a autumn-front end opening.

Low-heeled leather shoes fastened with shoe buckles were worn with silk or woolen stockings. Boots were worn for riding. The buckles were either polished metal, usually in argent (sometimes with the metallic cut into false stones in the Paris style) or with paste stones, although there were other types. These buckles were often quite large and one of the world'southward largest collections can be seen at Kenwood House; with the French Revolution they were abased in France equally a signifier of elite.

Hairstyles and headgear [edit]

Wigs were worn for formal occasions, or the hair was worn long and powdered, brushed back from the forehead and clubbed (tied back at the nape of the cervix) with a black ribbon.

The wide-brimmed tricorne hats turned up on three sides were now turned up forepart and dorsum or on the sides to form bicornes. Toward the cease of the period, a alpine, slightly conical hat with a narrower skirt became fashionable (this would evolve into the tiptop lid in the side by side catamenia).

Style gallery [edit]

1775–1795 [edit]

-

1 – 1776

-

two – 1775–80

-

3 –1780

-

4 – c. 1785

-

5 – c. 1785

-

half dozen – 1786

-

7 – 1780s

-

eight – 1788

-

nine – c. 1791

-

10 - 1790–95

-

11 – 1795

-

12 - 1790s

-

13 - 1793

-

14 - c. 1795

- Paul Revere'south shirt has full sleeves with gathers at shoulder and cuff, plain wristbands, and a small-scale turnover collar.

- Naturalists Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg Forster vesture collared frock coats and open shirt collars for sketching. The portrait depicts them in Tahiti, 1775–80.

- Captain James Cook in naval compatible, c. 1780

- Another portrait of Georg Forster depicts him in a collarless dress glaze and matching waistcoat with covered buttons, c. 1785. His shirt has a pleated frill at the front opening and his hair is powdered, c. 1785.

- Yellow wool suit with silk velvet trim shows the influence of English tailoring on European style.[22] Espana, c. 1785, Los Angeles County Museum of Fine art, M.2007.211.801a-c.

- Royal Navy officer and Governor of New Due south Wales, Arthur Phillip in a blackness clothes coat and tricorn hat, 1786

- 1780s suit of matching coat, waistcoat and breeches. The waistcoat is hip length, 1780s.

- Francisco Cabarrús holds the pop tricorne and wears a yellow-mustard suit of matching coat, waistcoat and breeches; the waistcoat is hip length, 1788.

- Baron de Besenval wears a short patterned reddish waistcoat with his grey coat and blackness satin breeches. His coat has a dark contrasting collar, and his linen shirt has plain fabric ruffles, Paris, 1791.

- French fashions of 1790–95 include a tailcoat of silk and cotton fiber plain weave with silk satin stripes, shown over ii layered figured silk vests. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

- The Duke of Alba, 1795, a portrait by Francisco de Goya, who depicts this nobleman wearing apparently colors in the newly fashionable English mode, although the duke still powders his hair. He is wearing long riding boots that reach the breeches.

- Relatively evidently men's suits from 1790s France. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, excessively ornamental styles were abandoned in favour of simple designs.

- French Revolutionary style, 1793: Édouard Jean Baptiste Milhaud, deputy of the Convention, in his uniform of representative of the People to the Armies, by Jean-François Garneray or another follower of Jacques-Louis David.

- Archduke John of Austria, the latest-born notable person to be portrayed wearing a powdered wig tied in a queue, c. 1795.

Extravaganza [edit]

-

Isaac Cruikshank'south extravaganza of a French revolutionary (1794), emphasizing striped wear and a Phrygian cap.

Children's fashion [edit]

In the belatedly 18th century, new philosophies of kid-rearing led to clothes that were thought particularly suitable for children. Toddlers wore washable dresses called frocks of linen or cotton.[23] British and American boys later on maybe three began to wear rather brusque pantaloons and short jackets, and for very immature boys the skeleton suit was introduced.[23] These gave the showtime real alternative to boys' dresses, and became fashionable across Europe.

-

1 – 1775–1778

-

two – 1775

-

3 – 1778

-

4 – 1781–83

-

5 – 1784

-

6 - 1784–85

-

seven – 1785–86

-

8 – c. 1790

- Queen Charlotte of Portugal as a kid.

- Baby dress made 1775 for a child of Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotte of Holstein-Gottorp.

- The cumbersome outfit of the young daughter of a French bourgeois, 1778.

- Miss Willoughby wears the loose, sashed white frock that is the English daughter'due south equivalent of the fashionable lady'southward chemise dress, with a straw hat, 1781–83.

- Spanish boy in an early skeleton conform with a circular frilled collar and waist sash, 1784.

- The family of Leopoldo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany and Maria Luisa of Espana, 1784–85.

- Marie Antoinette and her children on a 1785–1786 portrait, showing the change to loose ankle-length skirts for lilliputian girls. Her son wears a light blue skeleton suit.

- Immature William Fitzherbert wears fall-front breeches, a full shirt, and a narrow black stock, c. 1790.

Working-class clothing [edit]

Working-grade people in 18th-century England and the Usa often wore the same garments as fashionable people: shirts, waistcoats, coats and breeches for men, and shifts, petticoats, and dresses or jackets for women. Even so, they endemic fewer dress, which were fabricated of cheaper and sturdier fabrics. Working-class men also wore short jackets, and some (especially sailors) wore trousers rather than breeches. Smock-frocks were a regional style for men, especially shepherds. Country women wore curt hooded cloaks, near ofttimes red. Both sexes wore handkerchiefs or neckerchiefs.[24] [25]

Men's felt hats were worn with the brims flat rather than cocked or turned up. Men and women wore shoes with shoe buckles (when they could afford them). Men who worked with horses wore boots.[24]

During the French Revolution, men'south costume became particularly emblematic of the movement of the people and the upheaval of the aristocratic French gild. Information technology was the long pant, hemmed near the ankles, that displaced the knee-length breeches culottes that marked the aristocratic classes. Working-class men had worn long pants for much of their history, and the rejection of culottes became a symbol of working class, and later French, resentment of the Ancien Régime. The motion would be given the extensive title of sans-culottes, wearing the aforementioned as the working class. In that location was no culotte "compatible" per se, merely as they were turned into a larger symbol of French society, they had certain attributes attributed to them. In gimmicky fine art and description, culottes become associated with the Phrygian cap a classical symbol. French citizens on all levels of society were obligated to article of clothing the bluish, white and red of the French flag on their wearable, oftentimes in the form of the pinned the blueish-and-carmine cockade of Paris onto the white cockade of the Ancien Régime, thus producing the original cockade of France. Later, distinctive colours and styles of cockade would indicate the wearer's faction although the meanings of the diverse styles were not entirely consistent and varied somewhat past region and menstruation.

In the 17th century, a cockade was pinned on the side of a man's tricorne or cocked lid, or on his lapel.

-

Sweden, c. 1780

-

England, c. 1790

-

England, 1792

-

England, 1790s

- A maid in a well-to-do household pours soup from a pot. She wears a caraco jacket over a petticoat together with a protective apron and high heeled shoes with curved heels, painted past Pehr Hilleström

- Everyday solar day dress in England reflected fashionable styles. The man wears a glaze with stylish large buttons over a double-breasted waistcoat and breeches. His hat brim is non cocked and he wears a spotted neckerchief. The woman wears a green frock over a skirted jacket and petticoat.

- Two men at an alehouse wearable felt hats. The man at the right wears a short jacket rather than a coat.

- English countryman wears a circular felt chapeau and a smock-frock. The countrywoman wears a short ruby cloak and a circular chapeau over her cap, 1790s.

- Idealized sans-culotte by Louis-Léopold Boilly

Contemporary summaries of 18th-century fashion change [edit]

These two images provide 1790s views of the development of fashion during the 18th century (click on images for more information):

This caricature contrasts 1778 (at right) and 1793 (at left) styles for both men and women, showing the large changes in but xv years

This caricature contrasts the hoop-skirts (and high-heeled shoes) of 1742 with the high-waisted narrow skirts (and apartment shoes) of 1794

Notes [edit]

- ^ Dror Wahrman, The Making of the Modern Self (Yale University Printing, 2004)

- ^ Daniel Roche (1996). The Civilisation of Clothing: Wearing apparel and Mode in the Ancien Régime. Cambridge Up. p. 150. ISBN9780521574549.

- ^ Cissie Fairchilds, "Style and Freedom in the French Revolution", Continuity and Change, vol. xv, no. 3 [2000], 419-433.

- ^ Peter McNeil "The Appearance of Enlightenment pg. 391-398

- ^ James A. Leith, "Way and Anti-Way in the French Revolution," Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750-1850: Selected Papers (1998) pp 1

- ^ Aileen Ribeiro, The Fine art of Dress: Manner in England and France 1750-1820 (Yale University Press, 2002).

- ^ Anne Hollander, Sex activity and Suits: The Development of Mod Clothes (Knopf, 1994).

- ^ a b c Werlin, Katy. "The Chemise a la Reine". The Fashion Historian . Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b Weber, Caroline (2006). Queen of Way: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. Henry Holt and Co. pp. 156–175. ISBN0-8050-7949-i.

- ^ a b c d e Ribeiro, Aileen: The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France 1750–1820, Yale Academy Printing, 1995, ISBN 0-300-06287-7

- ^ Waugh, Norah (1968). The Cut of Women'south Clothes: 1600-1930. New York: Routledge. p. 72. ISBN0-87830-026-0.

- ^ "Eighteenth-Century Habiliment". fashionencyclopedia.com.

- ^ "Eighteenth-Century Wear". Style Encyclopedia.

- ^ Tortora and Eubank (1995), p. 272

- ^ "Victoria and Albert Museum: Shoe Buckles". Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Kohler, Carl (1963). A History of Costume. New York, NY: Dover Publications. pp. 372–373.

- ^ Digital History, Steven Mintz. "Digital History". Digitalhistory.uh.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-07-23. Retrieved 2010-04-20 .

- ^ Whitcomb, John; Whitcomb, Claire (2002). Existent Life at the White House: 200 ... – Google Knihy. ISBN9780415939515 . Retrieved 2010-04-20 .

- ^ "Work: Portrait of Archduke John of Austria (1782-1859)". Kunstost.at. Retrieved 2022-02-27 .

- ^ "Franklin and Friends". Retrieved 2006-03-xix .

- ^ Hollander, Anne (1994). Sex and Suits. Kodansha. p. 53.

- ^ Takeda and Spilker (2010), p. 42

- ^ a b Baumgarten, p. 171

- ^ a b Styles, The Wearing apparel of the People, pp. 32–36

- ^ Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal, pp. 106–127

References [edit]

- Arnold, Janet: Patterns of Fashion ii: Englishwomen's Dresses and Their Construction C.1860–1940, Wace 1966, Macmillan 1972. Revised metric edition, Drama Books 1977. ISBN 0-89676-027-8

- Ashelford, Jane: The Art of Clothes: Clothing and Society 1500–1914, Abrams, 1996. ISBN 0-8109-6317-five

- Baumgarten, Linda: What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Wear in Colonial and Federal America, Yale University Press,2002. ISBN 0-300-09580-5

- Black, J. Anderson and Madge Garland: A History of Fashion, Morrow, 1975. ISBN 0-688-02893-4

- de Marly, Diana: Working Dress: A History of Occupational Clothing, Batsford (UK), 1986; Holmes & Meier (US), 1987. ISBN 0-8419-1111-viii

- Fairchilds, Cissie: "Mode and Freedom in the French Revolution", Continuity and Alter, vol. xv, no. 3, 2000.

- Payne, Blanche: History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century, Harper & Row, 1965. No ISBN for this edition; ASIN B0006BMNFS

- Ribeiro, Aileen: The Fine art of Dress: Fashion in England and France 1750–1820, Yale University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-300-06287-7

- Ribeiro, Aileen: Wearing apparel in Eighteenth Century Europe 1715–1789, Yale University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-300-09151-6

- Rothstein, Natalie (editor): A Lady of Manner: Barbara Johnson'south Album of Styles and Fabrics, Norton, 1987, ISBN 0-500-01419-1

- Steele, Valerie: The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Printing, 2001, ISBN 0-300-09953-iii

- Styles, John: The Dress of the People: Everyday Manner in Eighteenth-Century England, New Oasis, Yale University Printing, 2007, ISBN 978-0-300-12119-three

- Takeda, Sharon Sadako, and Kaye Durland Spilker, Fashioning Fashion: European Apparel in Detail, 1700 - 1915, LACMA/Prestel Usa (2010), ISBN 978-3-7913-5062-2

- Tortora, Phyllis K. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume. 2nd Edition, 1994. Fairchild Publications. ISBN 1-56367-003-eight

- Tozer, Jane and Sarah Levitt, Cloth of Society: A Century of People and their Clothes 1770–1870, Laura Ashley Press, ISBN 0-9508913-0-4

- Waugh, Norah, The Cut of Women's Clothes: 1600-1930, New York, Routledge, 1968, ISBN 978-0-87830-026-6

Further reading [edit]

- Bourhis, Katell le: The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789-1815, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989. ISBN 0870995707

External links [edit]

- Glossary of 18th Century Costume Terminology

- An Assay of An Eighteenth Century Woman's Quilted Waistcoat by Sharon Ann Burnston Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

- French Fashions 1700 - 1789 from The Eighteenth Century: Its Institutions, Customs, and Costumes, Paul Lecroix, 1876

- "Introduction to 18th Century Men and Women'south Fashion". Mode, Jewellery & Accessories. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-12-09 .

- Looking at Eighteenth-Century Clothing past Linda Baumgarten at Colonial Williamsburg

- 18th century European dress at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art

- 1770s-1790s Style Plates of men and women's fashion from The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art Libraries

0 Response to "What Fashion Era Was Late 1700's"

Post a Comment